1826 - 1837

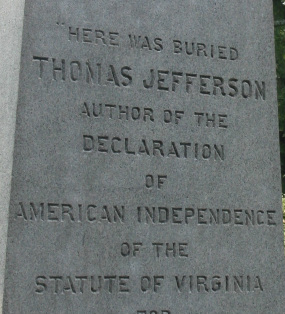

Jefferson died at the age of 83 on the Fourth of July, 1826. He was buried on July 5. His instructions for his gravestone were found on the back of an envelope. “On the grave, a plain die or cube of 3. F without any moldings surrounded by an Obelisk of 6.f height, each a single stone.

On the faces of the Obelisk the following

inscription, & not a word more

Here was buried

Thomas Jefferson

Author of the Declaration of American Independence

of the Statute of Virginia for religious freedom

& Father of the University of Virginia

because of these, as testimonials that I have lived, I wish most to be remembered. to be of the coarse stone of which my columns are made, that no one might be tempted hereafter to destroy it for the value of the materials.

On the Die Obelisk might be engraved

Born April 2, 1743 O.S. Died_____”

In his will, Jefferson conveyed the Monticello estate to Thomas Mann Randolph, Jr., his daughter Martha’s husband, and then in trust to Martha. He named his eldest grandson, Thomas Jefferson Randolph, as his executor. (A.C. Will Book 8, p. 248.)

No monument was erected upon Jefferson’s grave until 1833 and then it was not quite as he had instructed. The inscription was not directly engraved on the granite obelisk but into a marble slab attached to the granite. At the time of Jefferson's death there were 12 others buried in the graveyard, all relatives except for two–the wife of his blacksmith and the wife of a Florentine merchant who had come to Virginia to establish a wine industry.

Thomas Mann Randolph, Jr. died in 1828; early In 1829 Martha Randolph and her unmarried children moved from Monticello, where they had often stayed to their nearby home Edgehill to join her son Jeff (Thomas Jefferson Randolph). Unable to afford the crushing debts left by Jefferson, in 1831 Martha was forced to sell Monticello, the house and 522 acres to James Turner Barclay, but she retained the graveyard. Three years later, in 1836, Martha died and conveyed the graveyard to her son, Jeff (Thomas Jefferson) Randolph. (A.C. Will Book 12, p.270)

As for the condition of the gravestone, even though Jefferson had predicted that no one would destroy the rough stone, soon after the monument was installed, it became the object of vandalism. To prevent further vandalism, in 1837, after soliciting funds from the family, Jeff Randolph commissioned a 9’ tall brick wall to protect the graveyard. An iron fence spanning 8' to 10’ was built opposite Jefferson’s monument so that it could be viewed from the outside. (Robert H. Kean, History of the Graveyard at Monticello.)

On the faces of the Obelisk the following

inscription, & not a word more

Here was buried

Thomas Jefferson

Author of the Declaration of American Independence

of the Statute of Virginia for religious freedom

& Father of the University of Virginia

because of these, as testimonials that I have lived, I wish most to be remembered. to be of the coarse stone of which my columns are made, that no one might be tempted hereafter to destroy it for the value of the materials.

On the Die Obelisk might be engraved

Born April 2, 1743 O.S. Died_____”

In his will, Jefferson conveyed the Monticello estate to Thomas Mann Randolph, Jr., his daughter Martha’s husband, and then in trust to Martha. He named his eldest grandson, Thomas Jefferson Randolph, as his executor. (A.C. Will Book 8, p. 248.)

No monument was erected upon Jefferson’s grave until 1833 and then it was not quite as he had instructed. The inscription was not directly engraved on the granite obelisk but into a marble slab attached to the granite. At the time of Jefferson's death there were 12 others buried in the graveyard, all relatives except for two–the wife of his blacksmith and the wife of a Florentine merchant who had come to Virginia to establish a wine industry.

Thomas Mann Randolph, Jr. died in 1828; early In 1829 Martha Randolph and her unmarried children moved from Monticello, where they had often stayed to their nearby home Edgehill to join her son Jeff (Thomas Jefferson Randolph). Unable to afford the crushing debts left by Jefferson, in 1831 Martha was forced to sell Monticello, the house and 522 acres to James Turner Barclay, but she retained the graveyard. Three years later, in 1836, Martha died and conveyed the graveyard to her son, Jeff (Thomas Jefferson) Randolph. (A.C. Will Book 12, p.270)

As for the condition of the gravestone, even though Jefferson had predicted that no one would destroy the rough stone, soon after the monument was installed, it became the object of vandalism. To prevent further vandalism, in 1837, after soliciting funds from the family, Jeff Randolph commissioned a 9’ tall brick wall to protect the graveyard. An iron fence spanning 8' to 10’ was built opposite Jefferson’s monument so that it could be viewed from the outside. (Robert H. Kean, History of the Graveyard at Monticello.)

1836 –THE CIVIL WAR

In 1836, James Barclay sold Monticello to U.S. Navy Commodore Uriah Levy. The Levy family owned Monticello for 89 years. An ardent admirer of Jefferson, Levy was a fifth generation American, the descendant of an accomplished Portuguese Jewish family that arrived in the American colonies in 1733. He is best known for his fight for the abolition of flogging in the Navy, for courageous service in the War of 1812, and for overcoming considerable anti-Semitism to attain the Navy's highest rank. (Marc Leepson, Saving Monticello, 2001. p.55)

The Commodore cared for the estate until he died in 1862, when in his will he sought to leave Monticello to the people of the United States for the sole purpose of establishing an agricultural school to educate children of warrant officers of the US Navy whose fathers were dead - or if that failed, to the State of Virginia for the same purpose -- or if that failed, to certain Hebrew congregations for the purpose of educating poor children between the ages of 12 and 16. ( New York Times 3/23/1879)

Levy’s heirs disputed the will through many years of litigation, and during the Civil War the Confederate government confiscated the estate. It was during this twenty-year period that Monticello and the graveyard suffered the worst neglect.

A December 1, 1864 New York Times article commented: “the house and the monument have been sadly defaced and fragments carried off as trophies or mementos from a sacred shrine. Shame! Shame upon our thoughtless countrymen. Why should they be so disrespectful to the sepulcher of the great patriot of the Revolution?”

During the many years the Levy estate was in dispute, Monticello fell into near ruin. U.S. Congressman August Hardenburgh visited the house in 1878 and reported on the floor of the House of Representatives, during a debate about funding a monument for Jefferson's grave, "There is scarcely a whole shingle upon [the house], except that have been placed there within the last few years. The windows are broken. Everything is left to the mercy of the pitiless storm. The room in which Jefferson died is darkened; all around it are the evidences of desolation and decay." (Marc Leepson, Saving Monticello, 2001, p. 107)

This account of the decay of the graveyard is from The Charleston Mercury in August, 1861: “You climb, and climb, and climb . . . until you unexpectedly emerge in a small clearing around which a somewhat dilapidated, square brick wall runs. The iron gate is open, and as you enter, the eye glancing over a dozen or more marble slabs and head-stones rests on a granite pyramid, supported by a block of the same material, rudely hewn and blackened with age, which you know at once to be Jefferson’s tomb. There is no name on the monument, only the dates of birth and death. The conceit is a childish one and in wretched taste, and yet I cannot help thinking that the dusty incumbent who holds the stone in mort main is rather flattered by the surprise of his visitors. . . Around the great statesman, and philosopher and man of letters, lie his children and their offspring...”

There was no name on the monument because the family had removed the marble slab that held the inscription for safe keeping at Edgehill.

Go to Post-Civil War

In 1836, James Barclay sold Monticello to U.S. Navy Commodore Uriah Levy. The Levy family owned Monticello for 89 years. An ardent admirer of Jefferson, Levy was a fifth generation American, the descendant of an accomplished Portuguese Jewish family that arrived in the American colonies in 1733. He is best known for his fight for the abolition of flogging in the Navy, for courageous service in the War of 1812, and for overcoming considerable anti-Semitism to attain the Navy's highest rank. (Marc Leepson, Saving Monticello, 2001. p.55)

The Commodore cared for the estate until he died in 1862, when in his will he sought to leave Monticello to the people of the United States for the sole purpose of establishing an agricultural school to educate children of warrant officers of the US Navy whose fathers were dead - or if that failed, to the State of Virginia for the same purpose -- or if that failed, to certain Hebrew congregations for the purpose of educating poor children between the ages of 12 and 16. ( New York Times 3/23/1879)

Levy’s heirs disputed the will through many years of litigation, and during the Civil War the Confederate government confiscated the estate. It was during this twenty-year period that Monticello and the graveyard suffered the worst neglect.

A December 1, 1864 New York Times article commented: “the house and the monument have been sadly defaced and fragments carried off as trophies or mementos from a sacred shrine. Shame! Shame upon our thoughtless countrymen. Why should they be so disrespectful to the sepulcher of the great patriot of the Revolution?”

During the many years the Levy estate was in dispute, Monticello fell into near ruin. U.S. Congressman August Hardenburgh visited the house in 1878 and reported on the floor of the House of Representatives, during a debate about funding a monument for Jefferson's grave, "There is scarcely a whole shingle upon [the house], except that have been placed there within the last few years. The windows are broken. Everything is left to the mercy of the pitiless storm. The room in which Jefferson died is darkened; all around it are the evidences of desolation and decay." (Marc Leepson, Saving Monticello, 2001, p. 107)

This account of the decay of the graveyard is from The Charleston Mercury in August, 1861: “You climb, and climb, and climb . . . until you unexpectedly emerge in a small clearing around which a somewhat dilapidated, square brick wall runs. The iron gate is open, and as you enter, the eye glancing over a dozen or more marble slabs and head-stones rests on a granite pyramid, supported by a block of the same material, rudely hewn and blackened with age, which you know at once to be Jefferson’s tomb. There is no name on the monument, only the dates of birth and death. The conceit is a childish one and in wretched taste, and yet I cannot help thinking that the dusty incumbent who holds the stone in mort main is rather flattered by the surprise of his visitors. . . Around the great statesman, and philosopher and man of letters, lie his children and their offspring...”

There was no name on the monument because the family had removed the marble slab that held the inscription for safe keeping at Edgehill.

Go to Post-Civil War